ICONS: BLEU DE TRAVAIL

- Santeri Horst

- May 28, 2025

- 4 min read

There’s a certain kind of garment that doesn’t chase style. It shows up, gets worn, gets worn again, and keeps showing up until it becomes something more than clothing. Something built. Something lived in. An icon if you'll. Or just a French chore jacket.

It started in the fields. Then it made its way to the factories. And somehow, without ever trying, it ended up in the galleries, the ateliers, and the wardrobes of those who never lifted a shovel.

Blueprint of the Working Class

We got the first appearance of the chore coat back in the late 19th century. Industrialisation of the western world is well on its way, and the workforce needs to be outfitted. Before the industrial revolution most people wouldn’t differentiate the work and leisure wear, they wore what they had.

But with the industrialisation the demand for actual workwear grew. Just an apron didn’t cut it any more. The next gen workwear had to be more practical and even protect the worker to some extent. It had to be cheap to make and easy to mend. First the apron evolved into overalls, which then soon enough turned into pants and a jacket. At first the workers had to buy their own work clothes but the ever growing demand made the factories to began suppling its workers with new durable rigs. This change in the demand created a whole new workwear industry.

Built for Utility

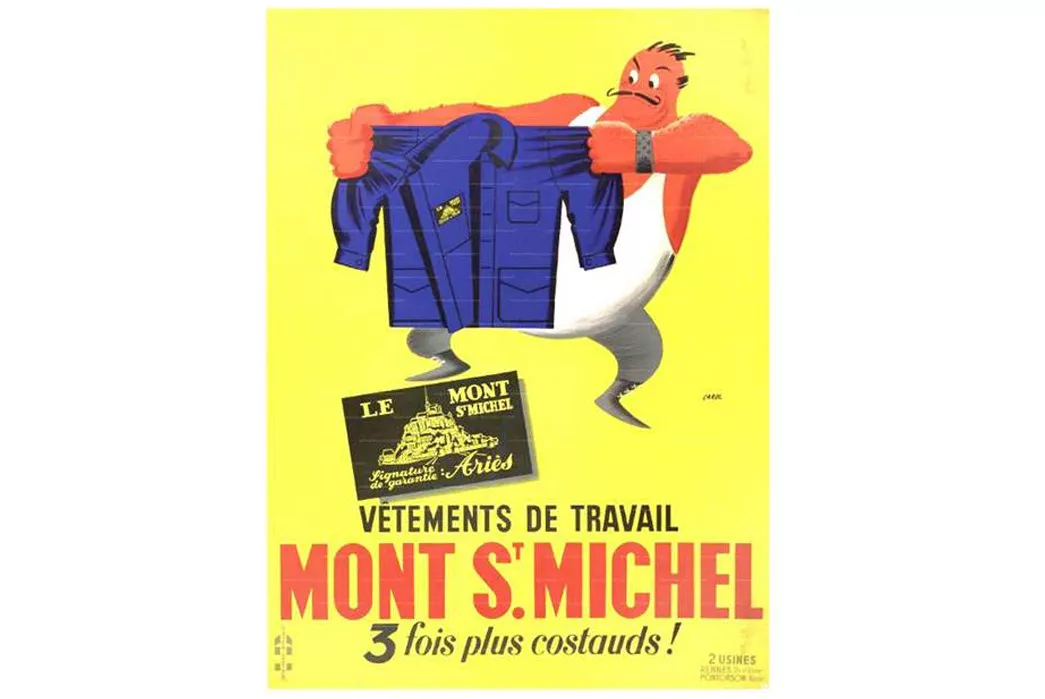

The French blue chore coat aka bleu de travail, literally "work blues", was never designed to make a statement. It was designed to disappear into the job. First appearing in the late 1800's, it was developed for French laborers, factory workers, railway staff and farmhands, who needed something rugged, practical, and repairable. French manufacturers like Le Mont St Michel and Adolphe Lafont began producing standardized outerwear with function-first design: roomy cuts for movement, reinforced stitching for strength, and deep patch pockets for tools and ciggies. Simple. Honest. Repeatable.

The fabric was workwear’s answer to armor: tough cotton drill, twill, or moleskin, resistant to snags, resistant to wear. Most coats were dyed a vibrant ultramarine, made possible by industrial indigo dyes that resisted fading and masked stains. The shade wasn’t an aesthetic; it was purely practical. But the color caught the light like wild fire.

Worn into Legacy

By the 1930s, the bleu de travail had become standard issue for industrial workers across France. It was everywhere, factories, railways, workshops, garages. As the country rebuilt after two world wars, the chore coat was part of the uniform that kept things moving.

And while the jobs changed, the jacket didn’t. The design stayed the same: simple, practical, reliable. That consistency is part of what kept it around.

And it aged beautifully. Each stain, tear, and sun-fade told a story. No two were alike. In an age before fast fashion, that mattered. But over time, it began to wander. Off the farms. Out of the factories. Into the Studios...

Into the Studios

Artists, always fluent in repurposing what already exists, were among the first chore coat adaptors outside the factories. Partly thanks to its utilitarian design and partly to blend in with the common people. From Picasso to Pollock it became a different kind of a uniform. Not out of irony, but because it made sense. It carried brushes just as easily as it once carried screws. It was democratic. Modest. Unfussy. Perfect for someone who created with his hands.

Other artists and intellectuals followed. The coat offered a kind of quiet rebellion, choosing the garb of workers over tailored elitism. It became a symbol of alignment with the working class, with manual craft, with ideas over aesthetics.

From Ateliers to Flagships

In the late 20th century, vintage pickers and subcultural stylists started hunting old workwear. The chore coat, sun-faded, frayed, authentically scarred, reached a new dimension. Utilitarian cool. Designers like Yves Saint Laurent and later, Daiki Suzuki (Engineered Garments), began referencing it directly. Japanese and American labels reissued near-identical versions. It moved from flea markets to flagship stores, but it kept its soul intact. The coat refused to become precious. It stayed rugged. It stayed blue. It stayed true.

Threads that last

Today, the French blue chore coat is more than a jacket. It’s a statement in silence, a canvas. Worn by baristas, painters, architects, graphic designers, and anyone else who values function over flash. Whether it’s layered over tees in Etu-Töölö or buttoned tight in a woodshop somewhere, it remains an emblem of honest design.

No logos. No gimmicks. Just the jacket, honest and blue. Still ready for work, even if you’re just riding the spora or hitting your local pub with your mates. Iconic because it never asked to be. Whether crisp or threadbare, it's never just clothes. It’s craft. It’s continuity. It’s still best worn with something to do, something to carry, somewhere to go. It isn’t nostalgic, it’s persistent.

If you want a coat that doesn’t speak loudly, but says everything. We just washed a our little blue suveniers from our trip to Paris and they are now available at your local vintage dealership. And we strongly recommend you to wear the hell out it, until it tells your story. Let it fade at the elbows. Let it tear at the cuff. Sew on a patch when it needs one. That’s the whole point.

Worn in. Never out.

Comments